I’ve been managing teams for most of my working life. For the first 7 years, it was simpler – working with a direct team and maximizing our output.

Then it got harder. As I first built my own company, and then focused on business development for other companies, it was no longer about just my team.

Instead, it was more about influencing other teams. Work with Marketing to plan the launch of a big partnership. Brainstorm with Product on the UX for the new solution. Burn the midnight oil with Engineering, to get the integration out by morning.

First reflection from all this – it’s not easy! (duh).

Leading your team requires answering a few questions, that are not straightforward. These are some of the questions I’ve had to grapple with over time:

- I’m a doer, but now I have to “manage” a team. Where should I begin?

- How can I make sure my team’s output is good enough, without micro-managing?

- I have a great team, but how do I get a solid day’s work out of them?

- I don’t have a team of my own, but I have to work with several different teams. No power, only responsibility ?. How do I drive output?

- How’s my team feeling? Are they happy with my leadership?

- Wait, what is my value-add as a manager?

These questions have become even more relevant now. Traditional face-to-face management is a relic of the fast-receding past. We now need to manage our teams remotely. And we need to remain effective, without micro-managing.

Second reflection: I realized that effective team management can be distilled into a few key principles.

Five to be exact.

Everything you’d read in an “Ultimate List of 100 Team Management Tips” derives from these core axioms.

Call them the Minimum Effective Dose, or the 80:20 of Team management.

And whether your team is with you in-person or working remote, doesn’t matter. The same principles apply.

Here they are, in order (TL:DR):

- Don’t make 100 decisions when one will do.

- Train your team, and give better feedback. Even when you don’t have the time. Especially when you don’t have the time.

- Delegate better.

- Fix things early. Run to fires before they start. And then prevent the next fire.

- Do better meetings (this one’s harder than it sounds).

Let’s go into each of these.

Before we jump in, a quick note: Would you like a cheatsheet for each of the principles below? (there’s a link at the bottom of the article too.)

(As a bonus, you’ll also get Sunday Reads, my weekly newsletter on business, entrepreneurship, and everything in between. Many say it’s the best email they get all week).

But first, let’s talk about the Manager’s Equation.

What is a manager’s output?

Regular readers of my writing know that Andy Grove’s High Output Management has had a huge influence on me.

One of the book’s main insights was the Manager’s Equation:

A Manager’s output = output of his organization + neighboring organizations under his influence

So it’s clear what you need to do as a manager. Increase the output from your team, or the teams you influence.

Now, there are a few ways you can increase output:

- Increase the size of your teams: More people = more output (but not really).

- Make your teams work faster: increase their productivity.

- Change the nature of work: do higher leverage activities.

The first option is never really available. The second option works, but hits its ceiling pretty fast.

The only long-term option you have is Option 3: focus your team on higher leverage tasks. Where there’s greater output per unit effort.

As Grove says,

To a manager, leverage is everything.

Your skills are valuable only if you use them to get more leverage.

High productivity is driven by higher managerial leverage. A manager should move to the point where his leverage is the greatest.

As we jump into the five principles, you’ll see the invisible hand of managerial leverage everywhere.

Principle 1: Don’t make 100 decisions when one will do.

Every day, we’re hit with a deluge of problems, opportunities, conflicts, questions – all of which require us to make a decision.

Yes. No. Reject. Accept. Counter-propose. Invest. Hire. Don’t Hire.

Making decisions is tiring.

Whether a decision is big or small, there is some overhead to making good decisions. You have to debate the choices, reflect on them, make the decision, and then follow-through to execution. Making decisions takes something out of you.

As a self-interested manager, it’s clear where you want to go – make fewer decisions, but get the same output. i.e., managerial leverage.

How do you make fewer decisions? By focusing not on tactics, but on strategy. Not on the chaos, but on the concept.

By not deciding on each specific choice you’re asked to make, but by laying out a principle for all such choices. So that your teams can make these choices on their own – you don’t need to decide on that topic again.

Why does this work?

As Peter Drucker says in The Effective Executive:

There are four types of problems

(i) Truly generic – current occurrence only a symptom

(ii) Unique for the organization, but happened to others

(iii) Early manifestation of a new generic problem

(iv) Truly exceptional and unique

Only one of these is unique.

Of the problems that you are asked to solve, almost all are generic problems with a standard solution.

So, as a manager, your approach to any problem should be to first assume it’s generic. Identify the higher-level problem of which this one is a symptom, and develop a rule or principle to solve that.

Assume a problem is generic, and develop a rule, policy, or principle to solve that.

I’ve seen this pay handsome dividends.

I head business development for a retailer of beauty products. Most days, my team is negotiating with brands that we carry, or brands that we want to carry.

Most negotiation impasses are standard. If the economics aren’t working, it’s due to 3-4 reasons. If the brand doesn’t agree on our purchase targets, there are again 2-3 ways to get on the same page.

When a new team member encounters such problems, I don’t just share the solution. I also make sure to talk through the logic while doing so.

- How to identify the underlying problem causing this impasse.

- How to resolve that specific type of problem.

- How to problem-solve together with the brand.

After a couple of turns through this process, they get it. The next time such a problem occurs, I only find out after it’s solved. Success!

To build leverage, always solve problems at the level of principle.

Remember: Decisions are an opportunity for managers to guide their teams on the right way to do things.

Make the effort to explain context to your team members. Even though you want to feel like Yoda and deal in one-liners.

You might disagree with me. You might say, sorry Jitha, I don’t have time. I’m busy fighting fires right now.

No. You ALWAYS have time to build leverage.

That’s how you prevent the next fire.

Before we move to the next principle, here’s a quick cheatsheet (you can find a link to download this and the other cheatsheets at the bottom of the article).

Principle 2: Train your team (all the time!), and give better feedback.

Training and giving feedback are very high leverage activities. In fact, they’re the highest leverage things you can do as a manager.

Why is that?

Let’s say a person in your team is struggling with modelling the financials for a new initiative. You spend 4 hours today walking through that with her. 4 hours = 10% of one work week.

If this improves her performance by even 1% every day, you keep reaping the benefit all year.

And like bank interest, this compounds too.

- Learning how to do one task often unlocks a new insight in another related task. Now that she knows how to model financials, she also does cost-benefit analyses better.

- She’ll also train her teams and stakeholders tomorrow, in the same way you have.

And all the benefit comes back to you! Remember the Manager’s Equation.

Training is a gift that keeps on giving. It’s like Amway, except it’s not a ponzi scheme.

Every conversation is an opportunity to train. Every decision (see principle 1) is an opportunity to train.

One of the most important tools for training is the performance review. Done well, it can give you a 10x team. Done not-so-well, you have a dysfunctional and demotivated team.

A few rules for giving feedback:

Rule 1: The only objective is to improve your employee’s performance.

Nothing else matters.

Rule 2: Measure the right things (outcomes).

A corollary of rule 1 is that you must focus on outward contribution. On results.

Efforts don’t count, outcomes do.

There are several advantages when you focus on outcomes over efforts:

- Everyone has a clear North Star to gun for. For someone in your Finance team, it may be “Hit the budget”. For someone in HR, it may be “Less than x% attrition this year”. No ambiguity. When everyone, from the most senior to the most junior, has the same values and goals, you maximize your output.

- It makes people management easier. If you told everyone, “Just work hard”, they would do their best to “look busy”. But if all that matters is output, then people will actually work hard. And on the right things.

- It unlocks more opportunities to learn. By framing the conversation on output, you pay less attention to visible effort. Instead of whining, “Jack doesn’t seem to be working hard enough.”, you wonder “wow, his output is great despite looking like he’s slacking. Maybe I can learn from him.”

OKR (Objectives & Key Results) systems are a great way to focus an organization on outputs. Measure what matters is a great book on the subject.

A word of caution: Choose what output you measure with care. It matters. A LOT.

I saw a great example of this at the lending fintech I worked with a few years ago.

For a long time, we tracked month-on-month growth in value of loans disbursed.

So, our sales teams focused only on the biggest loan applications – which were more complex and needed more paperwork and coordination.

Every month-end was a scramble to plead with the borrower to take the loan within 24 hours.

Then, one month, we decided to change the target metric to number of disbursements – i.e., your target is 20 loans, not $5M.

The nature of the company changed completely.

Earlier, there was little difference between us and a traditional lender. Now, we finally became the tech company we claimed to be. We became fast, we became energetic.

What gets measured gets managed. And What doesn’t get measured… almost doesn’t exist.

Rule 3: Focus on the right (few) areas in giving feedback.

Focus on a few major areas, where superior performance can lead to outstanding results.

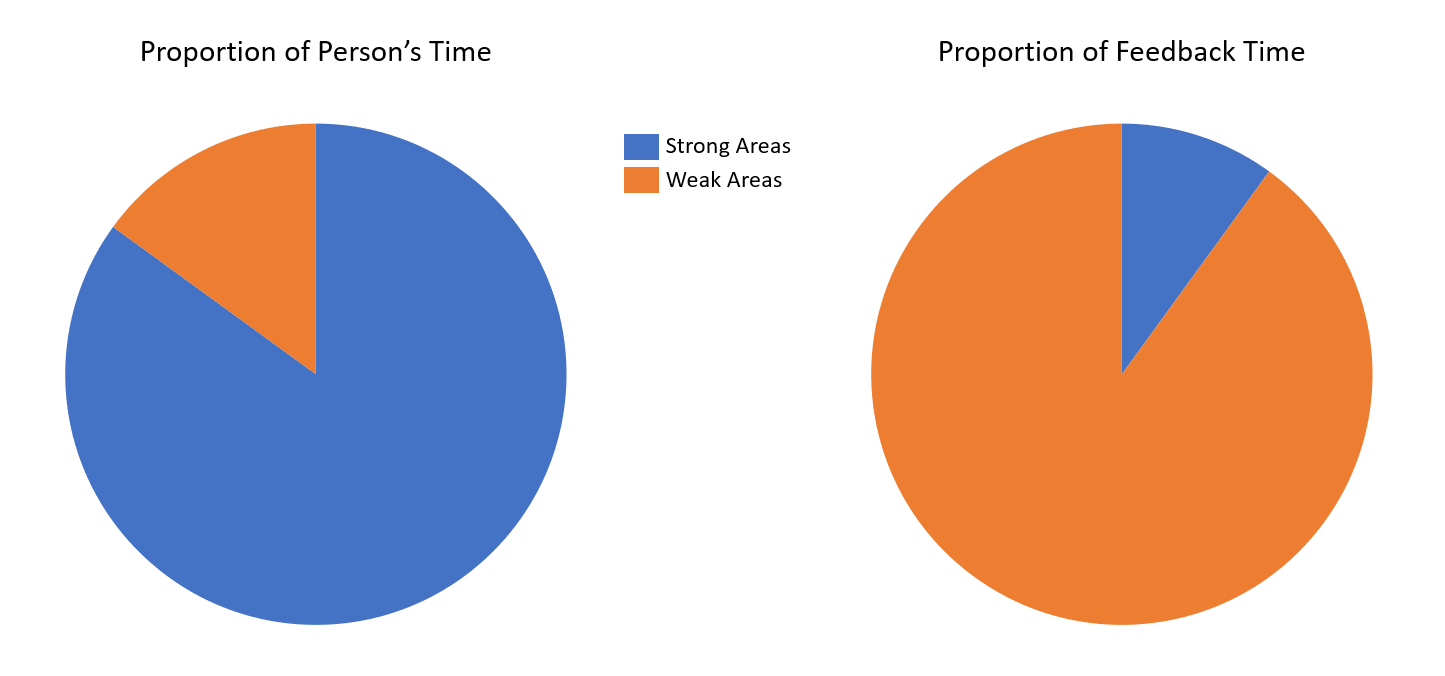

A good heuristic for this is: focus on strength development, not on removing weaknesses. Whereas our instinct is to focus on weaknesses instead.

It’s clear that the greatest scope for improvement is when you strengthen what someone is already doing well, so they can do it better.

Instead of asking, “What is she bad at?”, ask “what does she do well but can do better? What does she need to learn to excel at this?”.

Rule 4: Don’t tell them what to do. Ask questions instead.

Instead of pronouncing judgment on a team member’s performance, ask questions.

“Why did you choose this particular approach?” is far more useful than “you should have done this other thing instead.”

“What parts of this task do you find tough?” is far more useful than “you always screw up this step.”

Two other reasons why questions are better than assessments:

- You don’t have enough context of the details. Suppose there’s an obstacle there that you didn’t think of?

- It trains them in self-assessment. Next time, they’ll figure it out themselves.

And when you do have to instruct, offer suggestions, not orders. Remember principle 1, you want them to own the problem, rather than give it up to you.

Rule 5: “Ask one more question”.

You know the feeling. The call with your teammate is about to end, and it’s gone well. You feel like you’ve gotten through, and he has everything he needs to complete the task. There’s one tiny doubt that’s nibbling at the edge of your mind, but you let that pass.

No. Notice your confusion, and ask that one more question to clarify that.

You often learn that a simple question, which you almost didn’t ask, is the difference between flawless, on-time completion, and a week wasted on a wild goose chase.

This is particularly relevant when you’re working remote, and cannot catch non-verbal cues. As a friend told me, “The body language feedback of physical meetings is totally gone. And an over imaginative mind goes to town in its absence, dreaming up issues that might not exist.“

So ask that last question. It may be banal, but ask it anyway.

If you aren’t sure that the next steps are clear, ask, “Can you just play back the next steps, so I can remember them?” Or, “which of these pieces will you need my help on?”.

If you feel motivation is flagging, ask “how are you feeling?”. Or, “what’s the hardest part of this situation for you?”.

Rule 6: Don’t hand out the “shit sandwich”. Just don’t.

Here’s the cheatsheet, before we move ahead.

Principle 3: Delegate better.

You don’t notice poor delegation until you look for it. And once you do, it’s everywhere.

If you ever think, “I might as well do this myself. It would take too long to explain everything and check the person’s work.”, you’re delegating poorly.

If your team members keeps coming back to you with the same problems, you’re delegating poorly.

If you have to call every few hours to check how it’s going, you’re… you get the drift.

If you delegate poorly, you get zero leverage. You’re working crazy hours, wondering why you don’t have a life.

But if you delegate well, it’s like walking on water. You almost feel a little guilty at how effortless it is, yet everyone marvels at your speed.

So, how do you delegate like a BOSS? Three things to keep in mind:

1. What to delegate:

Delegate activities that are familiar to you.

Why? So that you can quality-check the work better.

The more familiar you are with a task, the more you know the stumbling blocks. You know the weakest link. So you check that.

In my company, I have a slight reputation for finding errors in detailed financial models. It’s not that I check every formula and every cell – I just know where, and how, to look.

There’s also a deeper reason for delegating tasks that are familiar to you. As Henry Ward says in A Manager’s FAQ:

Delegate the work you want to do.

Employees will love working for you. The work you want to do is probably the work they want to do, and they will be happy employees because of it.

You will grow. Most people want to do the work they are good at. If you delegate the work you are good at, the remainder will mostly be work you are bad at. You will struggle, suffer, and learn. That is where growth comes from.

You will train future leaders. They will see you doing the hard, miserable work that nobody wants to do. One day they will want to do it too. Not because they enjoy the work, but because they see you doing it as their leader, and they want to be leaders too.

2. How to delegate:

Successful Delegation = transmitting objectives + preferred approaches.

No more and no less.

Why objectives? Because you want to measure outcomes, not effort.

Why preferred approaches? To simplify the task and make it a generic and regular task, instead of a unique and irregular one. Work simplification is a very high leverage activity.

Wait, why can’t I just tell people what to do? Because the more responsibility you have, the less leverage you have.

3. How to monitor:

This is an area that a lot of us struggle with. And we conclude by delegating less than we should. Why delegate, if I have to spend the same time later anyway, checking everything?

Delegation doesn’t mean you check every step of the work, in effect repeating the work. But it also doesn’t mean you don’t check at all – you’re delegating, not abdicating.

How you monitor depends on your teammate’s skill at that specific task, or their task-relevant maturity (TRM).

| TRM | Description | How to monitor |

| Low TRM | New to the task + low skill | Give precise, detailed instructions. Monitor with more rigor; periodic check-ins to guide, encourage. |

| Medium TRM | Done this before + more ready to take on responsibility | Communicate goals and approaches. Offer encouragement and support. Check parts of output where weak; sense-check overall output. |

| High TRM | Done this before + Comfortable to deliver output | Sense-check output. Also do random deep check of 1-2 pieces (like factories’ quality-check processes – random sampling). |

As your team moves along the spectrum from Low TRM → High TRM, you can dial back the monitoring (but never down to zero).

And here’s a cheatsheet, so it’s easy to remember:

Principle 4: Fix things early.

Remember: Energy spent early has 10x payoff.

I’ve written about this before. Like direct marketers and Nigerian scamsters, managers need to qualify the funnel early:

Material becomes more valuable as it moves through the production process. So, fix any problems at the lowest value stage.

Let’s say you run an apparel factory. If the input cloth you received has quality defects, when would you rather find out? When the shirt is ready, or before the shirt goes into production?

Find rotten eggs early.

This is one of the biggest ways Project Managers support their teams in consulting.

In my teams, for example, we would agree upfront on what the output was, and when it was due. The team would create a “blank slide loop” on Powerpoint, with just two lines on each slide: the key analysis or takeaway from that slide. Once we’d aligned on that, I’d know that they are working on the right tasks.

Pay disproportionate attention early. Fix any problem at the lowest-value stage.

Principle 5: Do better meetings.

Meetings. The productivity killer. Can’t live with them, can’t live without them.

Meetings are the medium of managerial work. Whether it’s gathering information, delegating, sharing knowledge, or nudging, we need meetings.

How can we do better meetings?

Well, this is what I’ve realized after a gazillion meetings attended – with clients, with partners, with team members, with peers:

The way to do better meetings is not to do bad ones.

It’s a little like Charlie Munger said: “All I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I’ll never go there.”

You don’t have to be a meeting Jedi. There is no Six Sigma certification you need. All you need is basic “Meeting Hygiene”. Don’t do bad meetings, and that’s enough.

Here are the five rules of Meeting Hygiene:

Rule 1: Set up a meeting only if the issue cannot be resolved without one.

Five people in a room for an hour isn’t a one hour meeting, it’s a five hour meeting. Be mindful of the tradeoffs.

Rule 2: Be prepared for meetings.

Everyone attending a meeting should know the objective of the meeting. What are we trying to solve. What are the options at hand. What are the pros and cons of each.

If you’re organizing the meeting, always share a pre-read. And if you’re a participant, always read the pre-read before the meeting.

Always end a meeting with actions, owners and timing, so it’s clear what the next steps are.

Rule 3: Be early / timely.

I won’t explain this.

Rule 4: Don’t use meetings to make decisions.

Don’t defer decisions to meetings. Make a decision first, communicate it over long-form writing, and use the meeting to discuss divergent views.

Yes, I know this specific problem is complex. I know it will take you 30 min to write down the analysis, and you don’t have the time.

Do it anyway.

It’s better than a 30 min meeting with six people (180 person-minutes) going in circles.

As I wrote in Sunday Reads #90: How to communicate when working remote:

Writing makes meetings a last resort.

As you begin to write more, you always default to an asynchronous discussion (over email / chat).

An email thread makes it clear when you need a meeting. The email thread is 10 messages deep, but there’s no decision. Many people aren’t agreeing. Or they are saying, “Yes, I agree”, but then saying something completely incongruous.

It’s only then that you need a meeting.

Jeff Bezos’ six-page memos are legendary for good reason.

Rule 5: Meetings are not a spectator sport.

A meeting should have the minimum number of people needed. No more.

That’s all! Here’s the final cheatsheet:

Hope you found the article useful! Would you like the principles above as a printable cheatsheet?

(As a bonus, you’ll also get Sunday Reads, my weekly newsletter. If you liked this article, you’ll love the newsletter).

Further reading:

- High Output Management: Excellent book by Andy Grove on the subject.

- The Effective Executive: Peter Drucker’s best book

- A Manager’s FAQ

Thanks to Shashank Mehta, Jinesh Bagadia, and Srinivas KC for reviewing previous versions of this.