One of the most common Amazon legends is the story of the Fire Phone.

It was a proud project for Jeff Bezos and Amazon. Multiple years in development, several new technologies designed to wow the consumer.

It was also dead on arrival. A colossal failure.

Within a year of launch, Amazon had discounted it to 99 cents on contract. And taken a $170M writedown on inventory.

When reporters asked Bezos about the debacle of the Fire Phone, he said:

If you think Fire Phone is a big failure, we’re working on much bigger failures right now — and I am not kidding. Some of them are going to make the Fire Phone look like a tiny little blip.”

Even the book Working Backwards explains this as a false positive of the Amazonian way.

Amazon uses the Working Backwards process as a filter to decide what to build. This process is not guaranteed to succeed. For every AWS there’s also an Amazon Fire phone.

The Fire Phone story adds to the legend of Amazon. Be bold and go where no one has gone before. Win big, or fail.

But… it might not be true.

The actual story may have been all too banal. From The Inside Story Of Jeff Bezos’s Fire Phone Debacle

“We poured surreal amounts of money into it, yet we all thought it had no value for the customer, which was the biggest irony. Whenever anyone asked why we were doing this, the answer was, ‘Because Jeff wants it.’ No one thought the feature justified the cost to the project. No one. Absolutely no one.”

As one top product engineer put it, “Yes, there was heated debate about whether it was heading in the right direction. But at a certain point, you just think, Well, this guy has been right so many times before.”

Now, I don’t know whether Bezos had already transformed into Vin Diesel at the time…

But even if not – who could tell him he might be wrong? When he’d been right so many times before!

This is not an Amazon-only problem.

Telling your boss he’s wrong is sticky territory. He’s so confident in his view, how can you antagonize him? What if you get fired?

But there’s a more fundamental question first:

Why is your CEO so damn confident even though he’s wrong?

One of my learnings early in my career (I was in management consulting) was:

Confidence in expressing opinion ≠ confidence in opinion.

I don’t mean this as a criticism. It’s a necessary outcome of leading large teams, or working on high impact projects.

As I said in Why every organization slows down to a snail’s pace:

The likelihood of success of any multi-person project is dependent on two factors:

• Likelihood of everyone investing as they need to; and

• effect of organizational friction

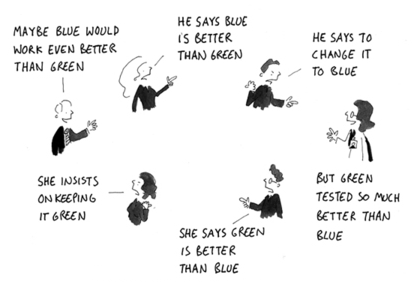

And organizational communication is like a game of Chinese Whispers.

Decisive communication is paramount.

There may be uncertainty in the environment. But once a decision is made, there should be no room for uncertainty in what needs to be done next.

You might say, “In an ideal world, people would express their opinion with probability attached.” For example, “I think we should raise prices. I’m 80% sure we won’t lose any customers.”

But this isn’t an ideal world. Even if the CEO is well-calibrated (which might not be a pre-requisite for success), what of the rest of the organization?

Will they just get confused? “Oh, so he isn’t sure that raising prices is a good idea”.

Like this comic from xkcd.

No, communicating to the rank and file of an organization isn’t a time for nuance. You make the decision as best you can, and communicate it without hesitation.

“Strong opinions weakly held” is almost a cliché now. But there’s a reason for that – it’s the only way to be decisive in uncertainty.

As my friend Ankit said in a conversation we were having just today:

Leaders have to be decisive in moving forward. At some point, you need to pull the trigger with conviction. Teams need some semblance of confidence.

And here’s the thing: Despite the outward bravado and confidence…

Your CEO knows he could be wrong.

When you make a decision about the future, you’re making a prediction (duh).

You don’t know how your consumers will react. You don’t know how your competitors will react. Hell, you don’t even know how your team will react.

But you’ve still got to make the decision. You’ve got to make a judgment call.

As Peter Drucker says in The Effective Executive:

An imperfect decision made in time is better than a perfect decision too late…

There’s a sharp line between deliberation and implementation: once a decision has been made, the mindset changes. Forget uncertainty and complexity. Act! If one wishes to attack, then one must do so with resoluteness. Half measures are out of place…

The wise officer knows the battlefield is shrouded in a “fog of uncertainty” but at least one thing must be certain: one’s own decision.

Even though your CEO communicates with confidence, he knows he could be wrong.

Just because the most senior person says something, doesn’t mean it’s right.

It is an opinion. A hypothesis. No more than that.

And an opinion can be wrong.

There’s a term for this: HiPPO, or Highest Paid Person’s Opinion. I first heard of it in Jeff Gothelf’s excellent article on the topic.

The article reminded me of an incident at one of my previous roles.

We were expanding to a new market segment, and we had a high target for the launch. 50 customers within the first 3 months.

I told my boss (the CEO) that we would need to hire a couple of people to make it happen.

He said, “No, I think you can manage it”. I nudged back a couple of times, but then took it on myself to deliver. After all, he was the CEO. He knew best.

Well, a quarter later, we missed our target.

When my boss asked me why, I told him again – it was because we were understaffed.

His next question was, “OK, why did you not then staff up?”.

Me: “Hey! You told me not to hire!”.

CEO: “Well, why did you not convince me otherwise?”

Me: <silence>

That’s when the penny dropped.

I don’t mean that he was unreasonable.

I mean: it was my job to get the decision right. If I didn’t agree with his view, it was my responsibility to push back.

If my boss makes the wrong decision and I know it’s wrong, then it’s my fault.

The CEO has a hypothesis. It’s the team’s job to test and prove that this hypothesis is valid.

One more thing…

Your CEO actually wants feedback.

Imagine you make a 100 decisions a day. All without enough data, but you can’t afford to wait.

You know you could be wrong, but this is not a school exam where someone will give you clear-cut feedback.

So you consider the situation, and make what you think is the right choice. If you’ve missed something, surely someone will tell you.

But guess what, no one does. Because they assume you’re right. You’re the most senior person and you’re so confident. You must be right.

In my experience, whenever I’ve pushed back to my boss (read the next section on how to this well), I’ve gotten a thought-through answer. With an invitation to push back again, if I disagree.

Sometimes I also see relief that someone is finally disagreeing with them. (I might be imagining this bit).

A friend of mine calls it “95% confidence, 95% flexibility”. That’s the mode in which many CEOs operate.

How to tell your boss he’s wrong.

Easier said than done, you say. “Your CEO might like feedback. But my CEO is different. He says things with absolute finality. No room to disagree”.

Fair enough, let’s talk about how to give your CEO feedback.

One of the Big Ideas of the book Never Split the Difference is: Calibrated Questioning.

When you want to persuade someone, you can do it by asking questions.

Not Yes/No or leading questions. People can see these a mile away. Everyone has met a fast-talking Amway seller.

Instead, ask more open-ended questions. Invite them to elaborate on their thinking a little more.

Some examples of calibrated questions to understand your boss’s POV:

- What’s the objective of this decision?

- I think xyz is an uncertainty with this decision. How do you think about this? How can we test this, before we move forward?

- How can we test this idea cheaply, before we implement it across the board?

- How will we know this idea is working at a scale worth deploying to our entire customer base? What metrics could we use?

Always bring in context and be specific.

If your question is broad, the answer will be broad.

As Tyler Cowen says about asking good questions, your question sets the bar for the answer. Set the bar high!

PS. Couldn’t find a way to fit this in, but it’s related. And funny.

PPS. If you liked this article, don’t forget to subscribe! Many say my weekly newsletter is the best email they receive all week.